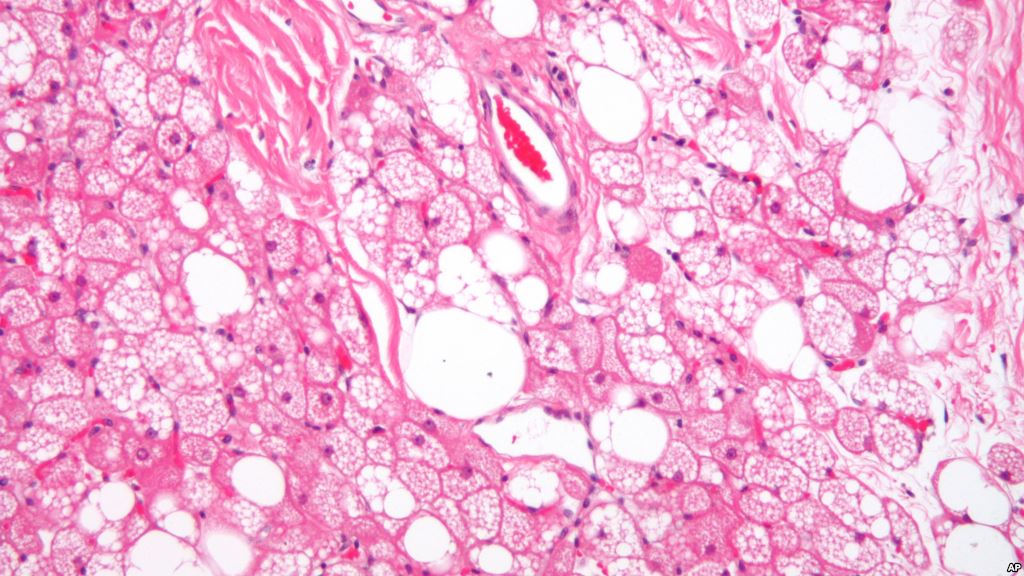

When it comes to skin infections, a healthy and robust immune response may depend greatly upon what lies beneath. In a new paper published in the January 2, 2015 issue of Science, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report the surprising discovery that fat cells below the skin help protect us from bacteria.Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, professor and chief of dermatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues have uncovered a previously unknown role for dermal fat cells, known as adipocytes: They produce antimicrobial peptides that help fend off invading bacteria and other pathogens.

Remember a time long ago when paintings depicted “Rubenesque” figures as a sign of health and prosperity? When being skinny signified pauperism, malnourishment and disease? And while today's obesity is a signal of malnourishment, brewing disease, and even poverty – it shouldn't be forgotten that mildly overweight people have been shown to live longer.

Modern medicine fervor, along with a bloated diet industry and a cultural obsession with zero percent body fat have once again dismissed a crucial necessity for some fat.

Demonizing all fat as shameful or “bad” must end. Fat under the skin – skin adipocytes – help protect against infections. Here is a study that shows the benevolent and helpful role that fat plays in our health.

Information from a press release follows – emphasized added:

Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, professor and chief of dermatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues have uncovered a previously unknown …

It was thought that once the skin barrier was broken, it was entirely the responsibility of circulating (white) blood cells like neutrophils and macrophages to protect us from getting sepsis.

But it takes time to recruit these cells (to the wound site). We now show that the fat stem cells are responsible for protecting us. That was totally unexpected. It was not known that adipocytes could produce antimicrobials, let alone that they make almost as much as a neutrophil.

The human body's defense against microbial infection is complex, multi-tiered and involves numerous cell types, culminating in the arrival of neutrophils and monocytes – specialized cells that literally devour targeted pathogens.

But before these circulating white blood cells arrive at the scene, the body requires a more immediate response to counter the ability of many microbes to rapidly increase in number. That work is typically done by epithelial cells, mast cells and leukocytes residing in the area of infection.

Prior published work out of the Gallo lab had observed S. aureus in the fat layer of the skin, so researchers looked to see if the subcutaneous fat played a role in preventing skin infections.

Ling Zhang, PhD, the first author of the paper, exposed mice to S. aureus and within hours detected a major increase in both the number and size of fat cells at the site of infection. More importantly, these fat cells produced high levels of an antimicrobial peptide (AMP) called cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide or CAMP. AMPs are molecules used by the innate immune response to directly kill invasive bacteria, viruses, fungi and other pathogens.

Gallo adds:

AMPs are our natural first line defense against infection. They are evolutionarily ancient and used by all living organisms to protect themselves.

However, in humans it is becoming increasingly clear that the presence of AMPs can be a double-edged sword, particularly for CAMP. Too little CAMP and people experience frequent infections. The best example is atopic eczema (a type of recurring, itchy skin disorder). These patients can experience frequent Staph and viral infections. But too much CAMP is also bad. Evidence suggests excess CAMP can drive autoimmune and other inflammatory diseases like lupus, psoriasis and rosacea.

The scientists confirmed their findings by analyzing S. aureus infections in mice unable to either effectively produce adipocytes or whose fat cells did not express sufficient antimicrobial peptides in general and CAMP in particular. In all cases, they found the mice suffered more frequent and severe infections.

Further tests confirmed that human adipocytes also produce cathelicidin, suggesting the immune response is similar in both rodents and humans. Interestingly, obese subjects were observed to have more CAMP in their blood than subjects of normal weight.

The human immune system is highly complex, relying on numerous types of cells to fight infections. Among the tools used by the human body to stay healthy are neutrophils and monocytes, which attack and consume microbial invaders. Epithelial cells, which line organs, and mast cells, which play a role in allergies, are usually the first on the scene at the site when an infection enters the body.

Mice were infected with staphylococcus aureus, a bacteria which commonly causes skin and soft tissue infections in humans. Researchers found fat cells increased in both size and number at the site of the infection, within hours of exposure. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP), a form of antimicrobial peptide (AMP), was produced by the dermal fat cells, partially protecting the mice from infection. When researchers studied mice who were unable to produce sufficient quantities of AMPs, particularly CAMP, they found the rodents were highly-susceptible to infectious disease.

Please Read this Article at NaturalBlaze.com

Leave a Reply